A few years ago I found myself protesting a certain national politician’s photo-op tour of a shelter for people who had been displaced to my city by hurricane Katrina. This particular visit seemed a little more self-serving and crass than usual, so much so that it had folks from all-kinds of political persuasions hrumphing a bit. I was certainly hrumphing. In fact, not that this was the first time, but I made have made a weeeee bit of a scene. Well, actually I am quite sure I did as I received a pretty direct smack down from the Bishop in the very next diocese-wide newsletter.

The reasons for the protest were simple: the need for assistance existed for a long time and in a belated response to public outcry, instead of support, Austin received a publicity tour. People displaced by Katrina felt it and the people of Austin felt it.

So it was all the more disappointing to arrive and find the local Bishop involved in what was believed to be an image-recovery campaign.

In my hubris I lost just enough of my temper and found myself shouting across the street and past barricades to the Bishop. I suggested, among a few small other things, that in this case, he was probably on the wrong side of the street. I felt strongly, and still do, that the Church must not sacrifice its prophetic voice for the appearance of power.

To be clear, however, I am not writing to defend my causes for protesting the visit or for crying out to the Bishop. The key moment of learning came for me a week later when I read the Bishop’s remarks.

In short the Bishop’s editorial in the monthly newsletter suggested that the guy shouting at the convention center (that would be me) was wrong for not being willing to, “set aside our differences and work for the common good.”

What the Bishop said is good, especially if I was heard as saying was that the Bishop was standing with the wrong political party. If we are only going to stand on opposite street corners and yell at the Bishop, “You should be here! You should be here,” then we would just be leaning into the very culture wars which I think are killing us softly.

But there was a second level of meaning in there I do no think the Bishop intended.

Are were to set aside our differences and work for the common good? Is this a good time to ‘agree to disagree’ and all just try to get along?

The longer I sat with this I realized that there are some differences between me and other people, other groups and ideologies, that I can not, and should never set aside. Not all of these convictions where I differ with people are mere party preferences or theories of how governments may or may not work. In fact, many of my convictions, with which others will often strongly disagree do not originate in my political tastes or preferences at all but in the stories that make up the narrative of what I have come to believe it means to be human.

Here are examples of differences I can set aside: Whether it is OK to ear white after Labor Day, whether or not one should drink red wine with fish, whether or not Dallas really does have a better or worse offense since last year, and whether it is more important to enroll a first grader in Mandarin or Spanish. I can easily set these differences aside, even when they feel really important to me.

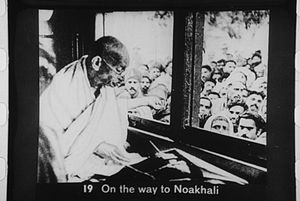

On the other hand it does not make sense for black people of today or 150 years ago to agree to disagree with others about slavery. Iraqi families with relatives in war zones should probably not agree to disagree about how soon peace should come. Gandhi was not willing to put aside his differences on whether it was ok to make his own salt. Rosa Parks should not have simply chosen to go find a bus that would let her ride how she wanted to.

I cannot remember a single time I remember any of the gospels saying, ” And Jesus spake saying thusly, ‘Well I just guess we have to disagree on this one my Pharisee friends.”

When we are talking about convictions about the dignity of human lives, enacting policies that will increase the suffering of others, or treating the lives of others as means to someone else’s ends, I can not, nor will I suspend our differences.

What I can tell you is that the story by which I live compels me to love you in those differences and to work with you for the good we can. I can tell you that I don’t find value in harming people, like you, who differ from me …and I can promise not to kill you.

My challenge has been to establish a cease fire in the culture wars. For some people this has made them rightly concerned that what I am recommending is a call to let things slide, to be less passionate or concerned, to find our lowest common denominator and stick with it.

When we talk about agreeing to disagree it is said as if it is the only way for people to move ahead in friendship without turning to violence; we have to learn to not care as much about important things. It seems as if we have to set aside our passions. A peaceful world will only be filled with people willing to suspend their convictions.

Passion is not the problem. The problem with the culture wars is that the drive us to a certain kind of certainty of who we are and who our enemies are and the battles we fight with each other so inject us with fear that we cannot imagine much else outside of either winning or losing. The culture wars steal our passions and replace them with anger alone.

As we live in the rhetoric and the thinking habits of the culture wars we become less and less cautious about the things we are willing to sacrifice in order to stay safe. We are willing to do this because the more carelessly we fight against each other the more fear we conjure.

The arduous battle for the identity of citizen’s identities have fooled us into believing, whether we admit it or not, that there are three kinds of people: Red, Blue, and Useless.

Neither the left nor the right have coherent moral narratives. They have platforms. These are platforms that people can agree or disagree with but that is all that they should be. Out political parties, despite the escalating culture wars do not provide us with sensible stories, narratives about what humans or for or what makes them flourish. Nor should they.

Christianity, for example, does not have a platform. It is a story of about the point of being human and what it means as humans to flourish. It is a story about God. But most people when asked to give an account of the Christian faith in the America often cite aspects of political platform.

Insofar as we let political platforms become the defining moral narratives of our lives, we become one whose identity is shaped more by the state than by any of the other identities we claim to be protecting. We ask for it.

Our platforms have indeed become our stories, which are stories of conflict, fear and competition in which no matter what happens in any given election, only a few will win. Fear will remain our most prevalent constant.

And so what we in fact need is not some sense of the lowest common denominator. Nor do we need more voices yelling louder.

What we need are people, and groups of people willing to tell their stories and more important, to listen to each other’s stories.

The only Christian response to the culture wars is to love our neighbors, love our enemies and pray for those who persecute us. If instead we have become a people who have relented to living our convictions in both certainty of ourselves and fear of others,whoever we think we are, we are no longer the same people who lived like Abel, Enoch, Noah, Abraham, Sara, Rahab, and the all star cast of famous “Faith” chapter of Hebrews. Those people of faith never relied on an election to let them be faithful to God.

We haven’t even had the election and yet we have already turned on each other.

This is what it means to have faith today. No matter who comes to power, no matter what law is passed, regardless of the consequences God will always provide a way for me to love. How sure am I of this? Far more certain to be willing to die than to kill.