Last updated on March 19, 2012

For some time it has been rumored that the children’s rhyme, “Ring around the Rosie,” was a creepy rhyme born during the era of the Black Plague. That may be more the stuff of legend than of history, but it also makes a little sense. For  when faced when imminent and pervasive death, humans, and children in particular, have interesting ways of coping. These little mechanisms also shine a little light on why it is such good news to have an Ash Wednesday to take pervasive death and darkness and turn it on its head.

when faced when imminent and pervasive death, humans, and children in particular, have interesting ways of coping. These little mechanisms also shine a little light on why it is such good news to have an Ash Wednesday to take pervasive death and darkness and turn it on its head.

As the legend went, the “rings around the rosie” were signs of the swollen lymph nodes, one of the surefire signs that one had the plague. The “pocket full of poseys” was the bags of garlic cloves people toted around to ward off illness. The ashes were, of course, from the mass cremations that followed the illnesses.

Now this interpretation may not be entirely accurate, but it is truthful in at least one poignant way: we all fall down. All of us.

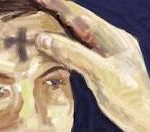

If the plague doesn’t get us, some other disease, or herd of penguins, or freak sink hole will get us, if not time itself. No one gets out alive. And once a year we stand in front of each other, touch each others’ bodies and say, “From dust you have come, and to dust you will return.”

Given the gruesome nature of other nursery rhymes and tales, the legend behind Ring around the Rosie is entirely believable. When faced with pervasive and imminent darkness we tend to do things to cope, including laughing at our predicament or throwing ourselves headlong into it. Dancing or dropping.

It can feel like the amount of violence, power-mongering, and just gunk in the world weighs on our times like the Black Plague once did. It is like we have deemed suffering and death a necessary evil within the world. We either laugh at its chaos or drop right into it.

In the Christian tradition we have called this darkness “sin.” It is a word that has been bandied about in some not-helpful, if not horrific, ways. Without love, our righteous indignation about “sin” is too easily wielded like a weapon to tear people down. However, naming sin without grace is not only cruel and deadly, it is dishonest.

No wonder we feel we a need to protect ourselves. So, we own it. “Yeah, I am a disaster. What can you do?” “I love sinning! I hate what is good.” “Don’t take me to Church. My head will just spin, and I’ll throw up pea soup.” Or it can be just as easy with the right group of friends to say, “Well X and Y aren’t really sinning. Everyone is doing it. It’s tolerable.” Of course the most deadly escape can be, “Well, at least I am not as bad as _____. I believe what is right. I get the important things. I am not so bad.”

Nowhere in these thoughts lies hope. In fact, these thoughts force us to settle and to side-step the possibility of transformation. We try to lower the horizon so as to not feel afraid or suffocated.

What is counterintuitive about Ash Wednesday is that it gives us profound hope. It is drenched with grace. It reminds us that we are not yet who we can be. And it reminds us that someday we will die. But it also reminds us that our fault and mortality do not have the final say on who we are before God. When God is in the mix, there is good news in finding out we have been wrong. Having been wrong means we live in the not-yet. There is – God help us – more.

It was not long ago that we were telling the stories of angels showing up to misfit shepherds and saying, “Be not afraid.” The message of Ash Wednesday is the same. You don’t have to fudge or reinterpret anything. “Don’t be afraid! Be fearlessly honest. Be entirely who you are. This is were we begin. I am with you. My name is God and I am not done with you yet.” The ashes of repentance are forged in the fire of God’s love.

“Always keep your death before you,” Benedict reminds us. He is not just being morose or dark. He is reminding us of our mortality. With that, we are reminded that God is not done with us yet, and is even about to do something new and unimaginable in us. There has never been a better time to dig up the garden and see what’s going on underneath.

We all fall down. It is not a call to abandon all hope. On the contrary, it means there is hope because we can begin right were we are – not where we wish we were. It just means we are all in the same boat.

Even as we move toward death, if we begin where we are, our best days lie ahead.

Amen!!